AstroSat Space Talks: Celebrating the launch fifth anniversary

AstroSat Space Talks with students who have worked with the data from various instruments of AstroSat, on the occasion of the fifth launch anniversary.

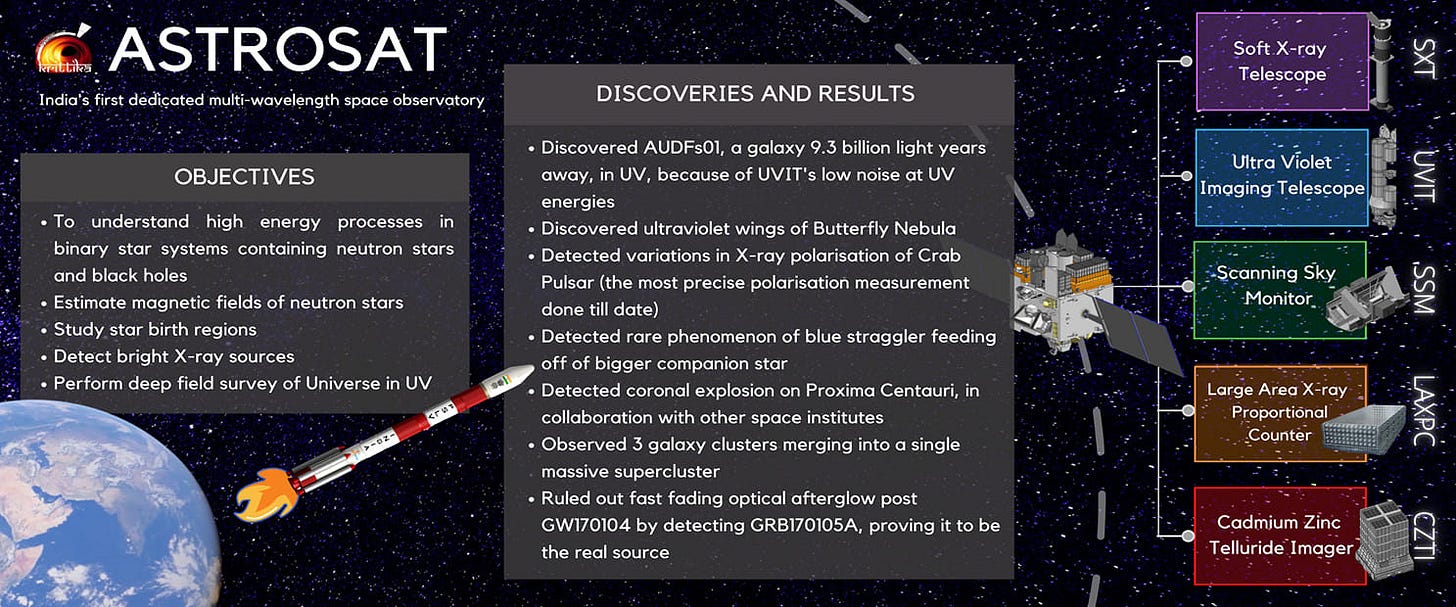

India's First Dedicated Multi-Wavelength Observatory, AstroSat, launched five years ago on this day into a 650 km orbit by PSLV-C30 from Satish Dhawan Space Centre, Sriharikota. This mission is aimed at simultaneously studying celestial sources in the X-ray, UV (Near and Far) as well as the optical ranges of wavelength. Over the years, it has generated an enormous amount of research through its multiple instruments. From discovering a galaxy in UV and observing the merger of three galaxy clusters, to making the most precise polarisation measurement till date, AstroSat has brought many laurels to the country.

I want to Congratulate ISRO and all academic centers that were involved in developing the payloads. In the last five years, many other institutions and students have become associated with the AstroSat Mission. To mark this occasion of the fifth anniversary rather than pointing out the spacecraft characteristics, I decided to interview a few students of Prof Varun Bhalerao. They have worked with data from AstroSat. So here is the AstroSat Space Talks.

How did you get interested in Astronomy?

Aditi

It was back in 5th grade when we had recently moved to Mumbai, when my parents took my sister and me to Juhu Chaupati, Hanging Gardens amongst other places along with Nehru Planetarium. It was the first time that I saw a 'Sky show' in a 'Sky Theatre'. It felt like all the planets, stars and galaxies had come to life glowing and moving through the inside of the dome of the theatre. This experience left me enthralled. Although I didn't know the term "Astronomy", I have been interested in it since then.

Akash

For me, Astronomy was sort of a background interest that always bugged me, but I never did acknowledge it until my Bachelor's. But once I did, there came an outpour of overwhelming desire which kicked it off. I started the usual way, reading off Wikipedia, for the basics, regarding any topic that accompanied in the process, attending Krittika talks, and watching youtube lectures. After everything I did, a talk or some material that I read, I used to do this 'thing', where I used to compile all that could remember and understood into some form of text and then try to build on it. For me, Astronomy was something that gradually grew on me over the years.

Drishika

I have been interested in astronomy since childhood. I would listen to podcasts related to astronomy, actively take part in Astro quizzes in school and college and follow up on space-related news. However, it had always been a passive interest to me. I considered it a hobby that I can practice throughout my life, but not something I can pursue as a career. The fact that I am pursuing Mechanical Engineering and not Physics convinced me that I am not qualified for a career in astronomy. But, this changed when I met like-minded people through the astronomy club in my college. People were studying wide branches of engineering, from metallurgy to electronics, but all of them were passionate about astronomy and worked towards seriously pursuing it as a career. That gave me hope. Over the lockdown, I learnt more about astronomy and Physics and transformed what I previously considered a passive hobby into a serious career option. I joined Professor Bhalerao's research group after this, to get a practical introduction to the world of astrophysics.

Arvind

My first exposure to astronomy was in my first year at the Indian Institute of Science Education and Research (IISER), Pune, through Prof. Rajaram Nityananda, our classical mechanics professor. The idea of how astronomy began fascinated me - from a curiosity to look at the beautiful night sky to calculating and predicting the motion of planets and other celestial objects for both social and scientific purposes. I was then introduced to amateur astronomy through the regular stargazing sessions organised by the Jyotir Vidya Parisanstha (JVP) in Pune during my stay at IISER Pune. It is so impressive that we can learn so much about our universe with the tools of astronomy and learn more about physics that will be impossible to conduct in a lab.

Pranav

I was a convener in Krittika IITB for 2019-20, through which I got a rough idea of what astronomy people do in the institute. I also took a course under Prof. Bhalerao on Astrophysics, which was quite interesting, and exposed me to the sub-fields in astronomy. After asking seniors about what work is done in the research group, I got interested in working in the group. I joined the group in the summer of 2020.

Yashvi

The usual, it started with watching discovery channel shows like cosmos and reading about astronomy from encyclopedias when I was a kid. Then I started reading up more seriously in high school, and I kind of knew what I wanted a career in.

Sujay

Around 4th or 5th standard, I came across the book "Aakashashi Jadale Nate" by Prof. Narlikar (it is in Marathi, the English version is called A Cosmic Adventure). This sparked my interest in it, served as a great introduction to astronomy during my school years and inspired me about science in general. Later, when I decided that I want to have a research career in science, there was no other obvious choice than to research in Astronomy / Astrophysics.

Vedant

My first introduction to astronomy was at the Astronomy Olympiad Camp, just before I joined IIT. After that, the great community at Krittika kept me interested in the field. The first time I actually considered astronomy as a career was during a seminar about GW170817 at the Physics Department, which I attended randomly; the idea that we could find out the origin of heavy elements, by looking at just one object in the sky was probably what caught me. I didn't understand a lot then (possibly even now), but it was enough for me to become a proper Astro-nerd.

Gaurav

Unlike many, it was only when I was selected for the Indian National Astronomy Olympiad that I looked up at the night sky. That encounter with the world of astronomy lasted only for about a couple of months, restricted due to the engineering entrance exams (JEE). A few months later, when I joined IIT Bombay for my Bachelor's in Mechanical Engineering, this interest started growing through the activities of the astronomy club (Krittika). Despite overloading with several other institute activities, I always used to find myself attending Krittika's events. While attending several of these talks that Krittika organised over two years, I had the chance to interact with many IITB seniors who were working on astrophysics research projects. To get a better first-hand idea in this field & its research, I sat through the introductory Astrophysics course taken by Prof. Vikram Rentala, and it immediately caught my eye due to its intuitive yet intricate nature.

It was around this period (towards the end of my sophomore year) that I realised my interest isn't just restricted to amateur astronomy. Still, instead, I wanted to explore this excellent field more. When the time came to choose between astronomy & other opportunities related to my branch, I decided to trust my instincts, step away from my major, and venture into the field of astronomy.

How did you get associated with Prof Varun Bhalerao?

Aditi

In my pursuit to learn more about Astronomy, I had started searching for professors under whom I could do a summer project and learn in a more formal environment. It was then when I came across Prof. Varun Bhalerao, and saw the fantastic work he is doing. I immediately sent across a mail to him expressing my interest. When he got back to me and offered me a project, it felt surreal.

Akash

During my freshie and sophomore years, Astronomy was always a 'side hobby' for me, whilst I concentrated on my majors (Aerospace engineering), with Astronomy gradually growing on me. But at the very start of my third year, I gave it a go and started writing to a couple of professors within IITB stating my interest and attaching the text that I compiled during the past two years. Fortunately, I received a quick reply from Prof. Bhalerao, who called me in. It was a short interview, in which he was essentially was trying to know if I could fit into his group and their style of work. And since I am writing this, I made it.

Drishika

I joined the AstroSat research group in early August this year. My job is to sift through the data captured by the Cadmium Zinc Telluride Imager (CZTI) aboard AstroSat, process it, and identify gamma-ray burst (GRB) detections from the false positives. I also work on CIFT, which is a user-friendly interface that maintains a database of the GRB detections till date, and I improve upon and develop other diagnostic tools for the interface that is used to process the GRB data. In the future, I need to integrate a Bayesian blocks algorithm that is currently in development into the CIFT interface. In the long term, my job is to continue detecting GRBs and maintain the interface.

Arvind

I learnt about Dr.Varun Bhalerao from a fellow senior at IISER Pune, who had started working with him when Dr Bhalerao was a Vaidya-Raichaudhury Prize Postdoctoral Fellow at the Inter-University Centre for Astronomy and Astrophysics (IUCAA), Pune. I started working with Dr Bhalerao from my second year at IISER Pune on small summer/semester projects. I have always enjoyed working with Dr Bhalerao, who is very encouraging and helpful, ensuring a better learning experience.

Yashvi

I was looking to work on a small astronomy project during the winter vacation of the second year, and I went for some advice to my fac-ad Prof. Pradeep Sarin. He told me about a young professor at IUCAA working on building a new telescope, and he wrote Prof. Varun an email asking if he has any projects, to which Prof. Varun never replied :P But he ended up joining the IITB Physics department next summer, and I immediately sought him out. He was already advising too many students, but luckily for me, those were some of the senior astronomy club members like Pavan Hebbar who gave me an excellent informal recommendation (Prof. Varun asks his current students about any new student that approaches him). And that's how I started working with Astrosat CZTI data to look for GRBs.

Sujay

I was attending the Astronomy and Astrophysics summer school in IUCAA where Varun (he was a post-doc in IUCAA then) gave a lecture about building X-ray telescopes which I found very interesting. At that time I was interested in doing something which involved experiments as well as astronomy. The summer school was for one month only, but I had two more months of vacation so I contacted Varun if I can work on a research project with him which involved astronomy instrumentation. At that time he was toying with an idea to build a complete automated telescope (now a realised project called GROWTH India telescope in Hanle, Ladakh) to follow-up electromagnetic counterparts of gravitation waves. So when I spoke to him about my interest, he offered me a project which involved doing some prototype testing of automation using a small amateur telescope in IUCAA. I continued the work even after the summer vacation was over and throughout my 4th year at IISER Pune.

Gaurav

Throughout my initial 'starry-eyed' period with this field, I was always fascinated by the amount of science that these astronomers can do with so little information. This made me adore the wonderful instruments that astronomers use more than other subtopics of this subject. Right around the period when I decided to shift to astrophysics, Prof. Varun Bhalerao joined as a faculty at the Physics Department, and luckily, his research interests included astrophysical instrumentation. Being the head of the astronomy club in my third year, I was in touch with Varun for several club activities (Varun himself being one of the co-founders of Krittika). What started as planning for an ambitious idea of setting up a research-class telescope in the campus, soon turned into discussions about a possible research project & luckily he had the perfect opportunity for me to work on.

Over the past three years, working with him has allowed me to dive into a diverse set of projects that included instrumentation & has covered a wide range of the EM spectrum. The wonderful experience that I had in his research group was one of the significant factors that I decided to continue working with him for my PhD. Having himself transitioned from a non-Physics major to graduate studies in Astrophysics, Varun's immense experience, guidance & mentorship has tremendously helped me transition from a Mech Undergrad to a PhD student in Astrophysics.

Can you detail your contribution to Astrosat Research?

Aditi

I have been working on the data from CZTI aboard AstroSat for more than a year now. I have worked on the search for Gamma-Ray Bursts in CZTI data and in the development of a user-friendly interface along with some auxiliary tools to facilitate the search of GRBs. Recently my work has been more focused on searching for a broader range of fast transients and developing the associated interface, CZTI Interface for Fast Transients, or CIFT, as we like to call it. I am also working on detections of bursts from a magnetar SGR 1935+2154 which are unique because of their association with Fast Radio Bursts.

Akash

My contribution to research using AstroSat comes mainly from a hard X-ray instrument aboard AstroSat called the 'Cadmium Zinc Telluride Imager' or colloquially known as 'CZTI'. I do X-ray follow-up of a wide range of transients, like Fast Radio Bursts (FRBs), Gamma-Ray Bursts (GRBs), Gravitational Wave (GW), and Neutrino events. It is essential to say, I look for simultaneous X-ray emission from any astrophysical source that 'goes off' and 'lights up the sky' in the electromagnetic wave regime. In terms of its sensitivity, CZTI stands in level with some of the best X-ray detectors in the world, which makes it essentially a key instrument in studying X-ray emissions. It roughly detects a GRB a day and hopefully, it will for the next 5-10 years.

Arvind

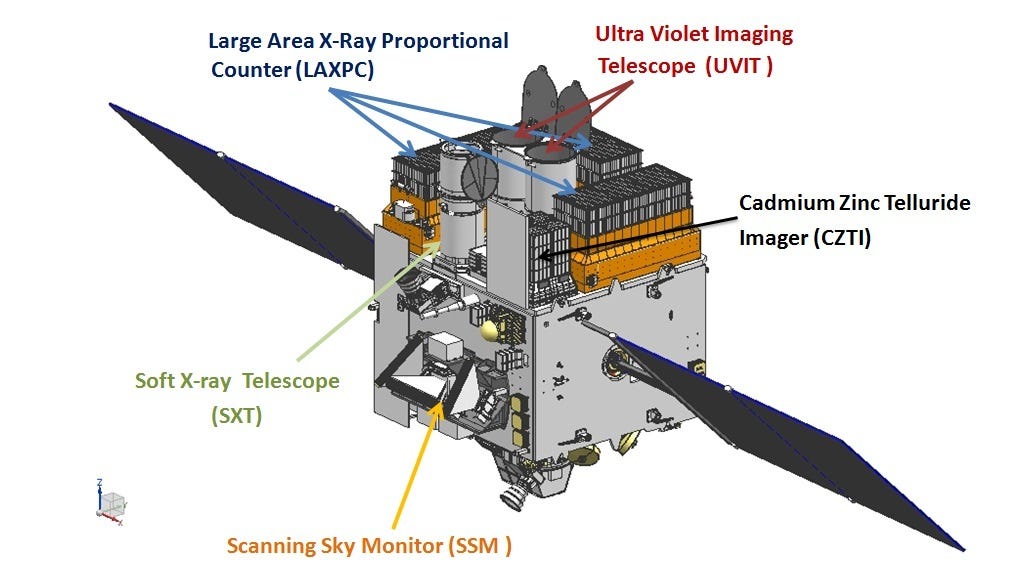

For my Masters Thesis, I worked on "Mass Modeling and search for transients with AstroSat: Cadmium Zinc Telluride Imager (CZTI)" with Prof. Varun Bhalerao. CZTI is a wide-field imager and uses a Coded Aperture Mask technique to image the sky in Xray bands (10 keV – 100 keV). CZTI can also be used to study transients as it functions as an open detector for photon energies above 100 keV. The detected photons can therefore be a result of reprocessed photons incident on various components of the satellite. Many of these photon interactions cannot be estimated analytically. So, a simulated model (Mass Model) of the satellite was built to understand the response of the detector to various types and locations of sources with respect to the satellite. My thesis work discussed possible methods to compare simulated and real data, which can finally lead to independent localising any transients by CZTI.

Pranav

My work involves searching for Gamma-Ray Bursts, significantly implementing an algorithm called Bayesian Blocks to see if the detection of GRBs can be improved. The data used is mainly from the Cadmium Zinc Telluride Imager (CZTI) onboard. We have currently three algorithms aimed at detecting GRBs, and this will hopefully be added to the pipeline. The algorithm generates custom time-binnings, based on the significance of the particular binning, and gives the optimal binning for a given time-series.

Yashvi

My work was focused on developing an automated pipeline to search for GRBs in CZTI data blindly. Until then, only GRBs reported by Fermi/Swift were searched for manually in CZTI data and reported on their GRB page. Since there was a lot of data, manually going through, it was not an option. So I employed a few statistics based algorithms to search for GRB peaks in CZTI light curves. I made the scripts to be completely automatic and also designed an interface to manage the saved GRB candidates. Through the pipeline, we found 40 new GRBs (in the archival data, I was able to process before I graduated). In comparison, there was an automated machine learning-based pipeline that was developed by IUCAA team which found ~20 GRBs in all CZTI data.

Sujay

I contributed to AstroSAT research in two different ways working on two different instruments. First, as part of my master's thesis, I worked on the Large Area X-ray Proportional Counter Detectors (LAXPC). An X-ray instrument (or telescope) like LAXPC doesn't respond to the incoming radiation at different energies in the same manner (e.g. lower energies are absorbed with greater efficiency). This is due to the intrinsic efficiency of the detectors and due to the extrinsic effects such as scattering due to instrument material. Hence to recover information about incident radiation from the detected data, it is essential to know the response of the instrument at different energies. My work involved simulating the instrument (using a software toolkit called GEANT4 which can simulate particle-matter interactions) and creating a response file which gives the response of LAXPC at different energies. This response file is essential for any kind of scientific analysis with LAXPC data. I carried out this work at LAXPC's Payload Operating Centre (POC) at RRI.

My second contribution involved modelling the entire AstroSAT !! The Cadmium Zinc Telluride Imager (CZTI) onboard AstroSAT is a hard X-ray instrument primarily designed to observe known energetic sources such as X-ray binaries, X-ray Pulsar and has a relatively small field of view (about 20 square degrees). However, due to the increased penetration power of X-rays at energies above ~100 keV, the collimators (vertical slats above the detectors used to block radiation from off-axis angles) become increasingly transparent, and the CZTI detectors can detect X-ray radiation from almost the entire sky (i.e. CZTI becomes an all-sky detector above ~100 keV). Due to this all-sky coverage, CZTI can detect Gamma-Ray Bursts or GRBs (most energetic and bright explosions in the universe) incident from all possible directions. However, any radiation coming from a direction that is not in the field of view of CZTI interacts with the AstroSAT elements (e.g. other instruments or satellite body) as well as the CZTI structural elements before hitting the detectors. Hence to be able to study any GRB detected by the CZTI, it is important to know the response of these structural elements to the GRB radiation. A detailed chemical and geometrical model of AstoSAT (called "mass model" as the actual mass of the satellite is simulated) is needed to estimate this response. My work involved creating this mass model using GEANT4 so that response of the satellite material can be simulated for a GRB incident from any direction.

Furthermore, the mass model is also useful to localise a GRB detected by CZTI using satellite elements as a coded mask. This is possible because, for a GRB incident from a given direction, the satellite material cast a unique shadow onto the CZTI detectors. Hence by simulating such shadow patterns and correlating them with actual CZTI data, GRB localisation can be achieved.

Vedant

I work on data from CZTI, the Cadmium Zinc Telluride Imager onboard AstroSat. High energy photons from astrophysical sources can essentially pass through the walls of CZTI and reach the detector, which is what happens during Gamma-Ray Bursts. This allows CZTI to detect bursts in a range of about 20-200 keV from several directions in the sky.

I work on two kinds of searches for GRBs with CZTI. One is a search using a few simple algorithms for peak detection (developed by Yashvi Sharma, B.Tech EP 2019) and scanning through candidate GRBs to vet them and select real GRBs. The other is a triggered search where we look at CZTI data at a particular time, when we know something interesting has happened, like a Fast Radio Burst (FRB), or a Neutrino event, or a Gravitational Wave detection. Searches for EMGW sources had been my main focus during the LIGO O3a, and O3b runs.

My work right now, along with Aditi Marathe (NITK), Drishika Nadella (NITK), Gaurav Waratkar (IITB), and Pranav Page (IITB), is based on streamlining this entire system, combining the two searches into a single interface, and developing CIFT: CZTI Interface for Fast Transients (cool name sponsored by me). In the future, this will allow for faster and smoother transient searches, and hopefully, help us sift (get it?) through the several hundred GBs of data from AstroSat CZTI to find those sweet GRBs.

Gaurav

There are several projects ongoing in our research group which are related to AstroSat (You can find all the projects that our group is working on at star-iitb.in). Here, I'll only summarise the projects where I have been involved over the past several months.

The Cadmium Zinc Telluride Imager or CZTI, one of the five instruments onboard AstroSat, is an excellent Gamma-Ray Bursts (GRBs) detector and has resulted in the detection of more than 300 GRBs since the launch of AstroSat in 2015. CZTI houses an array of 64 X-ray detectors that detect photons in the energy range of 20-200 keV. The large amount of data from CZTI makes manual searches for large spikes in the data (a key signature of GRBs) quite impractical.

To aid such searches, we are developing CIFT: CZTI Interface for Fast Transients, an interface that will control our automated pipelines to sift through the huge CZTI data hunting for transients. With several features like the ability to seamlessly integrate new different search algorithms as they are developed & facilitate the search for other transients through the same interface, CIFT will enable a much quicker turnaround in the search for GRBs as well as other transient sources like Fast Radio Bursts (FRBs) and the EM counterparts to Gravitational Wave sources.

To find even fainter/smaller real spikes of these GRBs, we have recently started a study on understanding the behaviour of the underlying noise in the CZTI data. This study has several long term implications. It will not only help in detecting very faint GRBs which otherwise our pipeline would have missed but also for constraining the emission models of other sources even when we do not detect the emission.

What are you currently working on?

Arvind

I am currently a PhD student at Texas Tech University, and I am working with Prof. Alessandra Corsi to study afterglow emission from gravitational wave sources and supernova remnants in the radio band of the electromagnetic spectrum.

Yashvi

I am working on finding bright supernovae (apparent magnitude m < 19) through Zwicky Transient Facility (ZTF) survey, and particularly looking at ultra long-timescale supernovae.

Sujay

My current work (as part of a PhD) concerns simulation and performance estimation of a GRB monitor instrument called ECLAIRs. This wide-field hard X-ray coded-mask imager will fly on the upcoming Sino-French mission called SVOM. The mission is dedicated to the study of GRBs and high energy transients. ECLAIRs is the primary instrument responsible for the detection and localisation of GRBs (and other high energy transients). The detection and localisation will be done in real-time using an onboard trigger (an algorithm that searches for GRBs or transients in the ECLAIRs data).

Because ECLAIRs has a wide field of view (FOV), it experiences a high background level which has an astrophysical origin. Furthermore, this background is variable due to the orbital motion of the satellite. Such variation can have an impact on the sensitivity of the onboard trigger. My work involves simulating a data (which involves the background variation) representing real observing scenarios and assessing the impact on the GRB detection sensitivity of the onboard trigger. Another part involves the development of an offline trigger algorithm which will be used to search for additional transients and GRBs once the data is downloaded to the ground.

Congratulations to you all for this massive success and happy birthday AstroSat! Thanks to AstroSat for helping us see the universe in a new light (literally!). And a big thanks to you all for finding the time for this interview - AstroSat Space Talks.